Meaning of the Veil

The modern, western construction of the veil as a symbol of oppression is made even more acute in its particularity, when we take into account meanings of the veil outside the modern, western world, or devoid of any specific cultural association. In its essential sense, veiling is the act of covering; the act of concealing something precious or sacred, usually from the eyes or minds of others. Veiling, therefore, has an inherent sense of mystery attached to it, which complements the spiritually inclined themes to which it is often attached. Historically, veiling has also been associated with class and respect. An Assyrian legal text estimated at around 1450-1250 BC states that veiling was compulsory for noble women, but not for servants, except when accompanying other noble women. From the same text, slave girls were forbidden to veil, and “hierodules” (sacred prostitutes) could only veil after marriage. In this context, the veil not only marked the upper classes, but signalled which women were under the protection of a man through marriage and therefore, not sexually available (Ahmed 1992: 15). The Assyrian tradition thus demonstrates a historical example in which veiling was linked to social stratification with dignifying value. Implied status was raised by the veil, not demeaned. Even in modern examples of veiling outside religion – whether in the form of veiling one’s car with a physical sheet, or in the drawing of house curtains – the concealing is not, by default, linked to any sense of oppression or subordination, but rather, to the intent of protection from the prying eyes of those who may be drawn to what should not concern them. A parallel can be made with the intent of pre-Islamic handsome Arab men, who would veil to protect themselves from the harms of envy, or women’s clothing in classical Greek society (550-323 BC), which served the function of concealing them from the eyes of strange men. In these instances, the common theme is that veiling is about the visual protection of what can be envied or desired, not about segregation or oppression.

Fadwa El Guindi (1999) comes to the understanding that the veil, far from being ‘indiscriminate, monolithic, and ambiguous’ can be appropriated to different cultural contexts to have different meanings from modesty and isolation to identity and political resistance. Similarly, Faegheh Shirazi (2001) points out that interpretations and representations of the veil across various cultures and contexts shows that its symbolic significance is constantly defined and redefined. This social constructionist approach to the veil gives the impression that its meaning is malleable according to whatever purpose is required: ‘the veil has been exploited by advertisers of Western products in the United States and in Saudi Arabia, by publishers of Western erotica, by filmmakers in the East and West, by Iranian politicians and clergy, and by militaries and militias in countries such as the United Arab Emirates, Iran, and Iraq’. To elaborate one example, Shirazi argues that many popular Bollywood films use the veil and the fantasy of hidden beauty to draw the male gaze by titillating the audience. There is a basic assumption that the female form has more power to arouse its viewer when it is veiled than naked. Both imagery and song lyrics are used to attract sensual interest to a veiled heroine who is beseeched by an eager hero desiring to see her unveiled. In such contexts, the veil is used as a means of sexual empowerment for the heroine, and as a tool for creating sexual tension in general (Shirazi 2001). This is in contrast with the veil in Iranian cinema, which, under the rules of state censorship following the Islamic revolution, prohibited the sight of uncovered female bodies in public and on screen. The veil is thus used to divert the male gaze away from sexualizing female characters. Both representations sit firmly within a spectrum of sexuality; one embellishing it, and the other obscuring it. For Homa Hoodfar (1992), the ability for the veil’s meaning to be changed and re-defined is in no way symmetrical between the East and West. She argues instead that the meaning of the veil in the West has been ‘static and unchanging’ while in Muslim cultures, the significance and social functions of the veil have varied tremendously, especially during times of rapid social change. She explains how some women in Iran have even used the veil to undermine certain men in their presence: while in dispute with a male non-relative, a Muslim woman might drop her veil to show that she doesn’t perceive him as a real man.

These expressions and functions of the veil challenge the blanket ‘symbol of oppression’ narrative that is commonplace in the UK and Europe, demonstrating the narrowness of the western discourse, and by implication, reflect the prevalence of the structures that keep such a discourse in place.

The Meaning of the Veil in Arab/Islamic Space and Culture

In considering such discourses surrounding the veil, it is important to emphasise the paradigm to which the Muslim veil is predominantly attached. In this vein, El Guindi allows the Islamic tradition to play an important part in dictating the meaning of the veil. In doing so, she stresses the “multiple dimensions”, that is, the different layers of meaning that can be attached to religious customs, seeing Muslims as living rhythmic lives, which alternate between the sacred and the secular. She combines these ideas with philosophical and sociological assumptions about the private and the public realm, highlighting how privacy in Arab and Islamic contexts differs from the secular, western context. Where privacy is usually understood as the right to not be intruded upon in the modern secular world, Islamic culture, for El Guindi, harbours an added theological dynamic whereby an individual or collective may be in some spiritual activity in communication with God, or be going about some relational (often gendered) activity with God in mind. From the women-exclusive private residential quarters of the harem typical to pre-modern Islamic Caliph residences, to the all-female dhikr circles of Sufi orders, the notion of gendered privacy has been a social fact of Muslim history:

Arab privacy does not connote the “personal” or the “secret” or the “individuated space.” It concerns two core spheres – women and the family. For both, privacy is sacred and carefully guarded. For women it is both a right and an exclusive privilege, and is reflected in dress, space, architecture, and proxemic behavior.

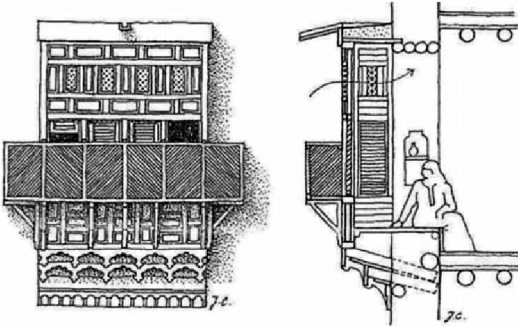

To see and not be seen: mashrabiyya in Islamic architecture

El Guindi also makes a comparison of the Muslim face-veil to “mashrabiyya” (lattice woodwork screens and windows) in urban Arab architecture, which serves to guard the family’s right to privacy. The creative sophistication of the wooden architecture permits the insider to see what is public, but denies the outsider visual access to what is private. This connotes a right to see and not be seen, rather than the sense of seclusion or social invisibility. But whereas the mashrabiyya is stationary, the veil is mobile and able to carry a woman’s privacy and sanctity into public spaces. Similarly, Bullock (2007) has argued that the hijab is not intended to stifle women, nor smother their femininity or sexuality, ‘rather, it regulates where and for whom one’s femininity and sexuality will be displayed and deployed’.

The dichotomy of public and private has been argued to be grounded in western European formations of society, and should not be imposed upon the Middle East. For El Guindi, Arab culture ‘is nuanced and dynamic, so much as to accommodate privacy in public’. The western polarity between public and private is too rigid and static to accommodate Arab and Islamic senses of space, which are characterised by a daily interweaving of the sacred and the mundane. She cites the example of the Muslim prayer, which can be performed in any location, instantly rendering sacred an otherwise ordinary space. Sacred space switches freely between the public and the private, meaning the appearance of a woman in niqab on the street is a normal sight, symbolic of this rhythmic and sacredly entwined way of structuring society.

Veiled Muslim woman in public

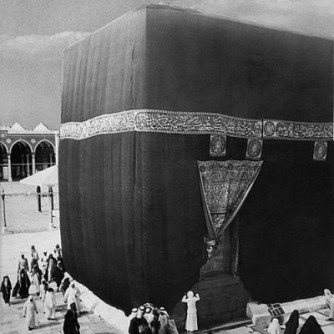

Further references to veiling are also found within Islamic literature, detached from subordination or even gender. The ‘ultimate veil’, draped over the House of God in Mecca (the Ka’ba) is a recurrent theme in classical Islamic literature, as is God’s Veil over Himself, which would otherwise burn the entirety of existence (hadith, Ibn Majah). Here, the veil is ascribed to the Divine, indicating the sublime and formidable power maintained within; while over the House of God, the veil is almost all one sees of it, serving as the ultimate visual manifestation that veiling signifies precious and sacred value. Amongst Muslims themselves, religious and spiritual reasons for wearing the face-veil or hijab – fundamentally, for the sake of a relationship with God – are generally overlooked in the media, yet clearly present in the answers of Muslim women in explaining their choice to wear it.

Veiling the House of God

In a ‘progressive’, materialist and secular society, ‘spiritual’ value attached to the veil is misplaced within the dominant culture. This aspect doubles the ‘absurdity’ of the veil insofar as it is both a covering – in a society that likes to reveal, and in that it has a spiritual notion in a culture where metaphysics does not inform public discourse. There is little wonder, then, why the veil’s sacred meaning is far removed from general non-Muslim consciousness and the mainstream media. Not being looked at or judged by commercial standards of beauty is another common reason offered by Muslim women as to why they feel more comfortable in hijab or niqab. This issue, in particular, concerns the tradition of the ‘male gaze’.

In the third and final part, I will consider the male/European gaze, and how this is deeply linked to modern western attitudes towards the Muslim veil. I will also highlight the relevance of a lost moral virtue: the ‘ethics of looking’ within the Muslim tradition, which is another necessary competent to understanding the place of the veil in public life.